YOU MIGHT HAVE seen Dr. Wael Khouli, his wife Michele, and their two young children taking leisurely strolls through downtown Marquette, along the lake front, or out at Presque Isle.

They seem like an All American family living a carefree, idyllic life.

Yes….and no.

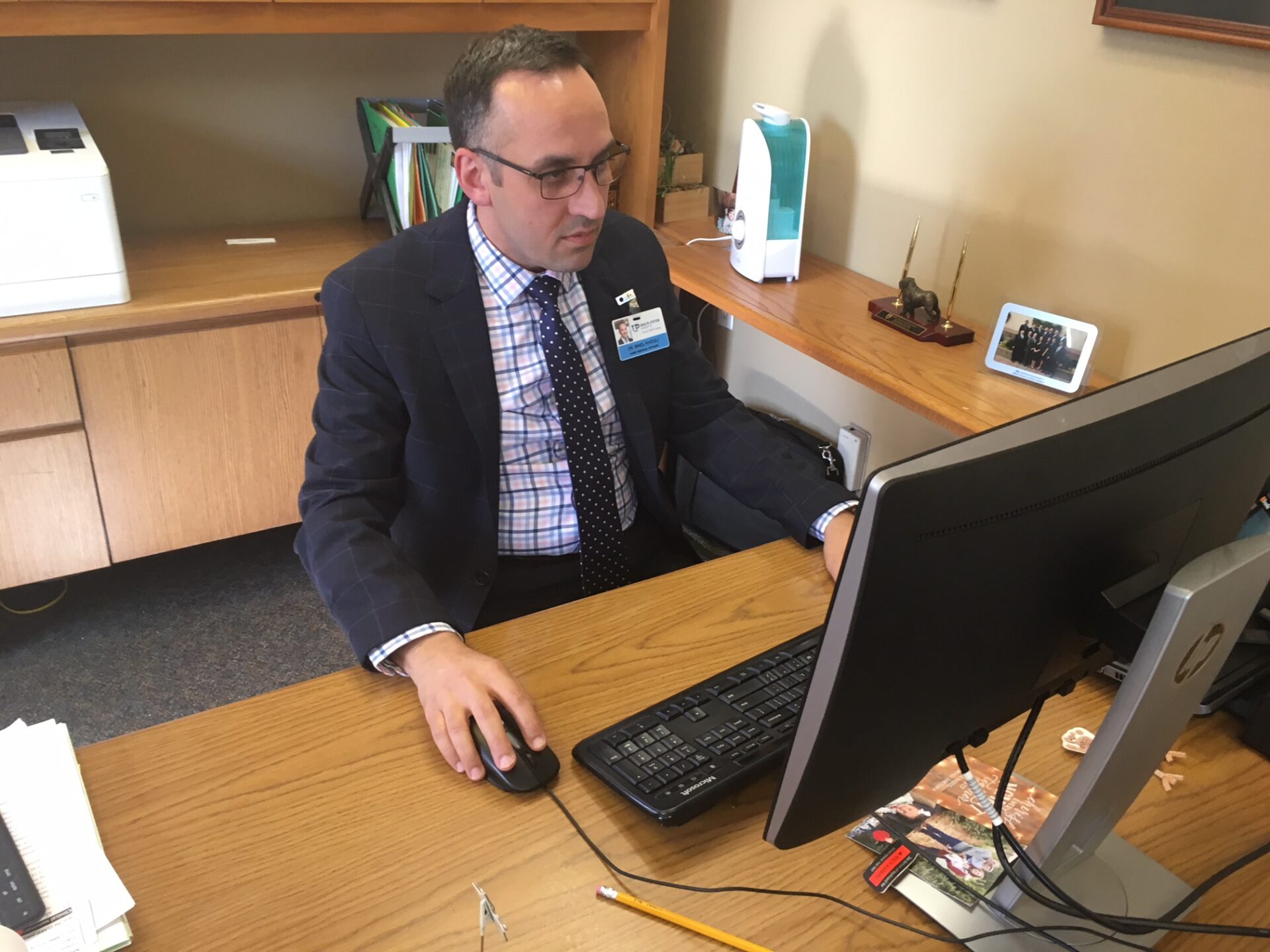

“I wish it was a bad dream,” Dr. Khouli tells you from behind his desk at UP Health System Marquette. He’s the Chief Medical Officer there. “Sometimes I wake up in the morning and think it might just be a bad dream. But it isn’t.”

You see, he’s Syrian. He left two his country two decades ago but he’s still got family there, and he still feels a strong emotional attachment to his homeland. But for the last seven years, it’s been a slaughterhouse. A half million people killed, 12 million displaced, a country left in ruins.

It started as a protest movement back in 2011, but then led to civil war, and then outside powers–the Iranians, the Turks, the Russians, ISIS, and, to some degree, Americans–all got involved. The ordinary Syrians were caught in the middle.

They’re still stuck.

Before the war, Wael (Dr. Khouli) grew up in a middle class neighborhood of Damascus, one of six children. His father died when he was only four, but the family made do with the father’s savings and help from relatives.

And his widowed mother stayed strong. “The two things she was very focused on was that she wanted her kids to be good kids, and she wanted us to be successful academically.”

Politics? Wael was curious when he was a boy but he mostly stayed out of it.

“We had a president (Hafez al-Assad) who always won with 99% of the vote,” he says. “It was a joke. The parliament was a joke. But you didn’t dare say a word. You didn’t dare think about challenging the government because there might be retaliation against you.

“I found out later that every high school class had an informant…You never knew who you could trust. You had to be careful. You couldn’t even tell a joke about the government.”

Assad died in 2000, but his son, Bashar al-Assad, took control of the government, and is now considered largely responsible for the devastation that Syria has suffered during the civil war.

Wael managed to steer clear of politics and got his medical degree in Syria. But then he started looking outward, to the United States.

“I knew there were more opportunities outside Syria, and there was…freedom,” he explains. “I was very intrigued by a what I saw outside. Although the media was very controlled, we watched western movies on VHS and we listened to pop music.” He smiles at the memories.

He served a residency in Ann Arbor, then began his practice in Gwinn about 15 years ago. And it was there that he met Michele, a Negaunee native who, at the time, was a pharmaceutical rep.

“Initially I thought I would most likely find a Syrian wife here,” he says, the smile returning. “I would not have thought I’d find my soulmate from Negaunee.” He laughs. “But I did.”

He proposed to her at the top of Marquette Mountain. They got married at Wetmore Landing on Lake Superior.

His career took them to Minnesota for 11 years but two years ago, with his appointment as Chief Medical Officer at UPHS-Marquette, they’ve returned to Marquette. They love it here, plan to raise their kids here.

He’s six thousand miles from his homeland. His mother and two of his siblings have also immigrated to the U.S. but many others in his family stayed behind.

He still manages to talk to them. “We talk on Skype and Facebook,” he says. “The government can’t keep track of everybody. We talk about everything that’s going on in their lives. There’s not much hope now. They just worry about getting along one day at a time.”

Wael hasn’t returned to Syria since 2009, but he sees the images and reads the stories on TV, the Internet, in magazines, and newspapers. Depressing. Does he see eventually going back for a visit–after the fighting, bombing and killing have ended?

“I don’t know,” he replies quietly. He pauses. “I don’t know if I’ll ever be allowed back. I mean, my name could be on a black list somewhere.”

It’s a bleak thought that fortunately can be brightened by springtime here in the U.P. And by strolls along the shores of Lake Superior, with the Negaunee gal who became his wife and his two little children who, he hopes, will never experience the horror and devastation of their father’s homeland.

You got news? Email me at briancabell@gmail.com