THE STUDENTS AT Marquette Alternative High School broke bread together Tuesday, celebrating Thanksgiving a little early.

More than a hundred of them enjoying food prepared by fellow students and their parents. Normal high-schoolers–in hoodies, hats and heavy jackets, some with radically colored hair, some with mismatched socks. Some quiet and contemplative, others chatty, and still others raucous.

Normal? Yes. But the school’s name does include the word “alternative.”

“These are kids who are looking for a place where they can fit in,” says teacher Nora Torreano. “A lot of them are good students but they just didn’t work out well in a regular high school environment.”

Some deal with psychological problems, others come from dysfunctional families, and many just feel uncomfortable in the social setting at a “regular” high school.

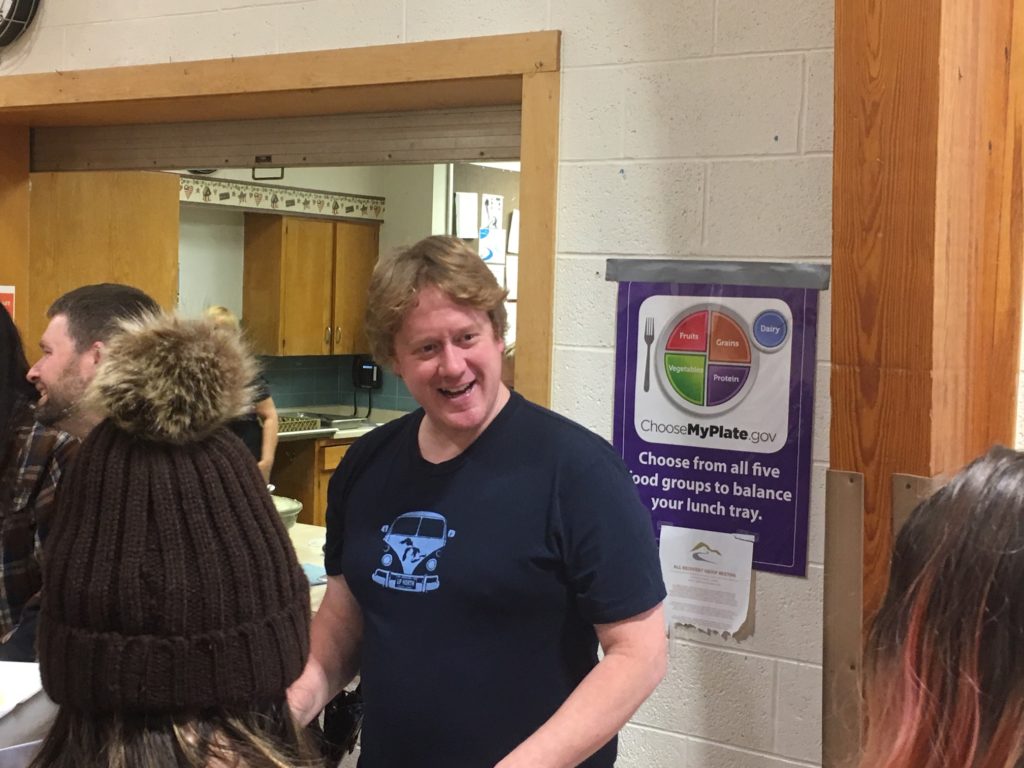

Here, it’s looser, more casual, more flexible. Principal Andrew Crunkleton is wearing jeans and a T-shirt today. The same with the teachers. No ties or dress shirts or dresses or expensive pants suits. Students call the teachers by their first names.

Much of the curriculum is the same–English, math, science, etc–but it’s taught in a less regimented manner. These kids have rebelled against regimentation, and likely would drop out if it was forced on them.

And they have other classes–Love Classes, they’re called–that include bikes, films, and books. Something they’re genuinely interested in. The school has a small hydroponic garden and a koi pond where the kids can pick up other skills.

But don’t misunderstand. This is not all fun-and-games. The students have to meet the states’s academic requirements to graduate, and although that will likely be fewer than half the kids here, without this school, virtually all of these kids would drop out.They’d be facing a life of rejection and failure.

That’s why on this day, these young people have something to be thankful for.

“Come on, my little squirrels!” Principal Crunkleton calls out to the students as he saunters down the corridor.

They gather in the “Family Room,” their meeting place. He urges them, about 100 students, to gather closer around him.

“I’m thankful,” he tells them, “because I was given the gift of teaching young people at a very vulnerable time of their lives.” He strolls around the room as he speaks, catching students’ eyes, smiling, speaking from the heart. “I treat all of you as family because you are my family.” He pauses. “All of us here have someone to be thankful for, someone we should say “Thanks” to for being a part of our lives. I want you to tell them that.”

He dismisses them, and they go back to their classes to write letters of gratitude. Some students have never even written a letter before. But they sit, pen in hand, serious and mostly quiet, deciding how to say thanks to that special person in their sometimes troubled lives. They finish, address the envelopes, and seal them.

They return to the Family Room, and Crunkleton asks if any of the students would like to share their private thoughts of gratitude with their classmates and teachers.

Twenty hands shoot up in the air, and they speak, one after the other.

“I was so totally screwed up when I got here,” one boy says. “I just wanna thank everyone for putting up with my bullshit.”

“I’ve had twenty mental breakdowns in your office,” a girl says to Crunkleton. “Thank you for listening to me.” He replies: “You can always have some more.”

“I’m grateful to all of you,” a boy says. “I really haven’t had a family to support me. You are my family.”

And on and on it goes, students expressing thankfulness to the crowd. No embarrassment.

Afterwards, 17-year-old Alex Durand sits down and quietly explains whom he wrote to: a teacher at the school, Brian Prill. “I haven’t had much support from anyone in my life, but he’s the one person I can open up to and he listens to me. I have OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) and it’s difficult. But he talks to me and tells me not dwell on the past, and he helps me control myself.”

Alex plans to joins the Marines when he graduates next spring.

Eighteen-year-old Kiara McLaughlin, who’s planning to go into nursing, wrote her letter of gratitude to her parents: “I’m just so thankful to them for not sending me away to a foster home. They’ve had to put with so much from me! When I first got to this school, I didn’t care about anyone–not them, not anybody, just me. But now I’ve changed.”

They’ve all changed, they’re all changing, as they navigate the treacherous waters of adolescence, at Marquette Alternative High School. And as they break bread together on this Thanksgiving, they’ve come to a realization: Life ain’t easy sometimes, but there’s always someone out there willing to lend a helping hand.

You got news? Email me at briancabell@gmail.com