HAVE YOU BOUGHT ANYTHING for a nickel lately? Probably not. A nickel doesn’t buy what it used to. I remember a pinball machine that you could play for a nickel. You could get a candy bar for a nickel. And if you had two nickels, the opportunities were endless!

Now… not so much.

But nickel… the mineral, not the coin, is worth a little more these days. And that’s what’s driving the continued operation of Lundin Mining’s Eagle Mine in Powell Township, and the associated Humboldt Mill.

The history of the mine goes back to 2002 when Kennecott Minerals discovered a rich body of copper sulfide ore just south of Big Bay, near the Yellow Dog River. The site is also in the vicinity of Eagle Rock, which the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community claims as a sacred site, culturally and spiritually important to the Ojibwa. Also in the area is the Huron Mountain Club, a private hunting and fishing retreat, restricted to members and guests.

Initially, opposition to the mine came from those local entities, as well as environmentalists from all over. Protests were staged and a lively public debate ensued involving those against the mine for environmental reasons and those who favored it due to its economic possibilities.

After a number of fits and starts, the mine finally happened. And it’s still happening today, nine years after the first ore was dragged out of some very deep holes. At some point, due to market influences, the focus changed from copper to nickel. And now, with the growth of electric vehicles, nickel has become even more valuable as it’s a component in EV batteries.

The first projections suggested a ten year lifespan for operations, but as the geologists continue to find new veins, the drills keep churning. Now Eagle managers are predicting a 2027 closure date, but that too is flexible. If they find more profitable ore, they’ll keep the mine open indefinitely.

Interestingly enough, one of the arguments in opposition to the mine was that ownership could only guarantee the existence of jobs for ten years. As we roll past that, the question should have been asked… “Who guarantees jobs for more than ten years.” Anybody?

Here’s where we’re at today. The two main factors when appraising the impact of the mine are… has it been a positive economic influence on the area, and have the owners lived up to their assurance of environmental stewardship?

To the former… absolutely. Hundreds of employees, a large percentage local, make good money and enjoy the kind of benefits most would love to have. And Eagle Mine’s annual contributions to community projects and non-profits… seven figures worth, benefits us all.

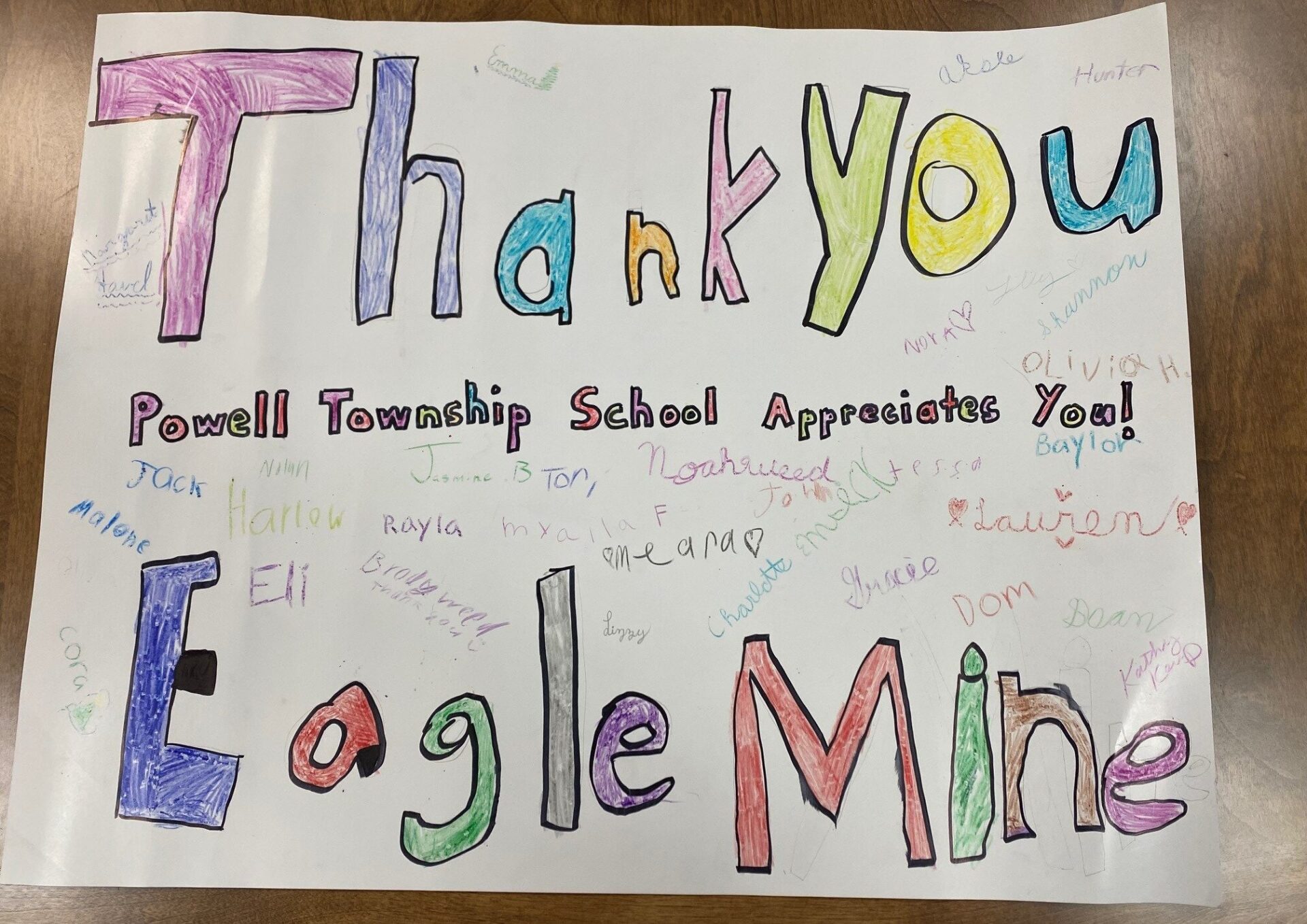

One contribution, which wasn’t even in the budget and didn’t get much ink outside of Big Bay, was a check written by Eagle Mine to cover some unexpected expenses related to a boiler failure at the local school. The check was big enough to also upgrade some furniture and other equipment. The check? Two HUNDRED thousand bucks. That’s a lot of nickels.

Regarding the environment, the independent Community Environmental Monitoring Program (CEMP), administered by the Superior Watershed Partnership and the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, has kept a close eye on the operation and files regular reports, available at the SWP website. However, unless you have a deep understanding of how to read very scientific reports, you won’t know any more than I did after examining the data.

Geri Grant, a member of the Partnership’s technical team responsible for oversight/implementation of the monitoring program, had this to say about their work… “There have been no major issues, however SWP and Keweenaw Bay Indian Community staff continue to monitor/track any changes observed in environmental monitoring results at Eagle Mine and the Humboldt Mill.”

She summarizes their results… “Eagle Mine has been attentive to the environment as well as open and transparent regarding their environmental performance.”

Other than the more than 40 trucks a day that run from the mine to the mill, through our neighborhoods and business districts, any negative impact on the environment in Marquette County seems to be fairly insignificant. At least, that’s my take. And when the mine finally does conclude operations, plans for reclamation of the land are already in place.

It should be noted, mine ownership wanted to build a road from the mine, through the northern Marquette County wilderness, more directly to the mill, but, for better or worse, regulators wouldn’t approve it.

The early opposition to the mine brings back memories of the protests that came about when the U.S. Navy announced the construction of a submarine communications grid near Republic, some four decades ago. Initially called “ELF,” the project went through a series of name changes and altered plans before it finally got the go-ahead in 1982 and began operations in 1989. The plug was pulled in 2004, and we haven’t heard much about it since.

We’re currently going through a similar situation with the proposed Spaceport, coincidentally, also in Powell Township. The Spaceport would certainly carry considerable environmental impact, which, in and of itself, shouldn’t be a deal breaker. Every project that comes about results in some level of impact. But does the environmental cost justify the results? In the case of the Spaceport, one important question looms… is it something we really need, or is it simply the product of some creative profiteering?

Regarding the Eagle Mine, the fact remains… where the U.P. has natural resources, be they minerals or timber, there will be an effort to monetize those resources, and that generally doesn’t happen unless there’s a need. As it stands now… we need nickel and wood. And as long as mining and logging operations are performed responsibly, we should be able to accept a measure of well-managed environmental inconvenience.

If you’d like to find out more, and get a first-hand look for yourself, Eagle Mine and the Humboldt Mill offer free tours, June through September. To register, visit eaglemine.com/tours.